Achieving success or a record performance is a great and memorable accomplishment for every coach. However, knowing the reasons behind such success and having the ability to replicate it from year-to-year and athlete-by-athlete is one of the keys to successful coaching. It requires an understanding of the principles that influence the athlete’s progress. In this article, I wanted to discuss the issue of the “boundaries of success”, the numbers behind the success, which will help you to compete and stand apart from your competition “There is no such thing as good luck, only good maths, and science!

Sergei Beliaev, Ph.D.

Founder of Super Sport Systems

Recently Andrew Mering published a very interesting review and analysis on Division 1 women’s teams progress (ability to improve personal bests times between seasons across all schools) (https://swimswam.com/who-got-faster-improvement-at-womens-d1-conference-meets/#author )

Top 16 Division 1 Women’s Teams on Progress Achieved During the Season

This information inspired us to conduct similar research, using the information provided by coaches using 3S. By using Andrew’s data as a reference, we can compare progress achieved by 3S coaches. We believe that group progression numbers not only reflect on the quality of coaches’ work, but also help set targets and progress requirements all coaches may aspire to in their work if they are aiming to compete for the top places in their conferences.

In our study, we analyzed the progress of individual results of FSU and Duquesne swim teams (both teams had successful seasons, where Dave Sheets, Duquesne Head Coach, earned another “Coach of the Year” award). We compared these numbers with another 3S program, at a club level (Randy Walker, Wyoming Green River), to view the differences between progress ranges in collegiate and age group athletes.

Discussions

We realize that successful performance at a top national level in conferences like SEC or the Big 10 depends on many factors, one of them being the initial level of athletes (recruiting factor) which can give a program an obvious and quite important advantage. However, we suggest that with relatively even distribution of talent among schools in the US, the following factors can be also significant and are necessary to demonstrate competitive performances at the national level:

- quality and precision of the training process

- ability to achieve constant individual progress from season to season

- ability to reach the best performance at a most important time in the season

And, if this assumption is valid, we then need to strive to reach the top boundaries of possible individual progress at any age level.

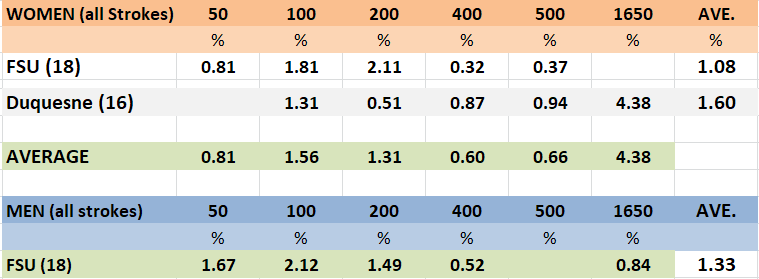

The analysis of individual progressions made by collegiate team members by distance (with the understanding that talent distribution can be different between schools and dependent on specific year recruiting strategy and its success), offered the following rates measured as a percent of improvement between previous season-best times and current season final performances at a conference or NCAA championship level:

We realize that combining all strokes together may skew the picture (S. Dormehl, S. J. Robertson, and C. A. Williams, 2016), however, in our case practically all female athletes reached their peak performance age. Also, the result’s samples were taken only from the best athletes in each stroke and the number of samples in each stroke was not enough to be statistically valid.

Before we jump into a deeper discussion, I would like to highlight that 14 out of 18 FSU women (78%) and 16 out of 18 men (89%) achieved their personal best times this season, totaling 27 best times among women and 46 among men.

To give our results a different perspective, it also should be noted that FSU team produced seven NCAA automatic qualifying times, set two school records on women’s side and six school records for men this year. We can suggest that results and progress rates we discuss are highly competitive and close to maximum individual effort in each case.

The average season progress rates between schools are between 1.08% (1.21 median) for FSU and 1.6% (1.53 median) for Duquesne. The Duquesne median rate of improvement is 0.3% higher than the highest median among all Division 1 schools according to our data. Please note that in our case all freshman times are included into account, unlike in the study made by Andrew Mering where freshmen times were not available and therefore not counted for. Such progress in our opinion can be attributable to two main factors:

- the lower relative level of athletes in that school (and therefore higher growth potential) and,

- better attention to the training needs of athletes (the result achieved through the application of 3S tools and training methods) and higher quality of training process management.

This rate of improvement across all distances and strokes placed Duquesne above the top rated by SwimSwam research Ohio State team and helped secure them a Championship title, suggesting that achieving this rate is necessary to be highly competitive at a conference level.

Reviewing the “reference” rates of improvement kindly offered us by Andrew Mering’s research, we can state that only four teams (Ohio, LSU, VA Military and Holy Cross) achieved 1.2 median progress with only one school (other than Duquesne, which is not included in Andrew’s report), Ohio State – another 3S user, reaching 1.3% average progress across the team. The fact highlighted in Mering’s report is that more than half of Division 1 women’s teams are in negative territory and did not demonstrate positive team results improvements at all, suggesting that their training process and management may have not delivered the intended results.

It can be suggested that individual relative progress rates of a winning team should be similar or even lower at top level conferences due to an expected plateau in performance given the level of results and age of competitors (Sokolavas, 2006). The difference in average progress rates between Duquesne and FSU (and other schools) can be explained by the absolute level of results achieved (the closer is the result to the absolute maximum, the lower is the individual progress rate).

In our analysis by distances, the Duquesne team “underperformed” in shorter distances (100 and 200), but reached better improvements on longer distances. It is especially true if we look at the progress rate of FSU male sprinters, averaging almost 2% improvement – a remarkable result given the age and level of results on short distances. These results are very typical of 3S swimmers, as 3S principles of training are often associated with a better ability to develop “functional” abilities, important for performances on longer distances, from 200 and up. However successful application of 3S principles in the case of Neal Studd (FSU) suggests that these principles can work equally as well with sprinters.

The average progression rates demonstrated by swimmers in our review do not tell the whole story. In our study, it was interesting to see the maximum values of progress achieved, since these numbers are better related to the absolute maximum possible rates of adaptation during one season time. In several instances, we recorded between 4% and 8% of improvement over the season, which is quite a significant rate at this age and level of competition. In our observation, a group of more talented swimmers (viewed by their relative results), were able to respond better and averaged over 2% of progression this season, which is also quite remarkable, especially in comparison with other schools averages.

It should be noted that these progression rates were achieved while using 3S training protocols and suggestions consistently from season to season for the last several years by both teams. In that sense, the training principles and strategy applied during this past season was no different from previous seasons. This is actually very important since this demonstrates the consistent growth which can be expected and achieved with 3S protocols.

As we work with athletes of practically all ages, we collected similar information from athletes swimming for a club (Green River, Wyoming, Coach Randy Walker). The progression rates achieved by swimmers at early age groups (10-14) are significantly higher compared to the collegiate level, which is consistent with the theory of diminishing return (L. Matveev, 1968) and “development corridors” concept (A. Vorontsoff, 2000; S. Gordon; 1978; G. Sokolavas, 2006).

The rates achieved by coach Walker are within or higher than the suggested Progress Rates at Threshold Age (12 years old) S. Dormehl, S. J. Robertson, and C. A. Williams, 2016. However, the individual variability of progression within age and strokes can be also very important.

The ability to maintain high progression rates from season to season in early development ages is important if we want to give our athletes competitive advantage at later times, collegiate, national and international levels. Therefore, the adherence to “progress standards” by age in our view should be a requirement from a national sport development perspective. Establishing the plausible development corridors and training principles that guarantee such progress becomes a necessity and a logical way to approach coaching and training in general, giving each participant the maximum chance to improve and achieve his athletic dreams.

Conclusions:

Based on our experience and the data analysis as provided above, we can conclude that a structured and optimized approach to training and sound training principles produce positive and stable progress in the vast majority of athletes at any age. The continuous participation in sports training, however, reduces the rate of progress with time spent in training, reaching 1-2% a season (and even less) at the very top level. Achieving such progress gets more difficult with time and requires very efficient and precise training methods. In that sense, precision is the key to success, which is essentially true at any age. Following this logic, it is just as important to pay attention to individualization at early periods of a swimmers development to help maximize the chances to reach absolute top results in the future.

At a collegiate level of competition (19-24), our review shows that in order to be successful and win, the group improvement rates should be within 1-2% per season.

To achieve the desired performance level at collegiate ages, the swimmers should be able to grow 8-10% per year starting from the beginning of their involvement in sport and until “Threshold age at peak performance”, which is around 17 years old for women and 18 for men (S. Dormehl, S. J. Robertson, and C. A. Williams, 2016). The individual rate of progress per distance and stroke can be viewed as an indicator of talent in a particular activity or sport, understanding that progress rates on longer distances are easier to achieve in the majority of swimmers. There is clear evidence that true talent tends to respond better to an “optimized training” approach even after reaching relatively high levels of results.

The group progress rates, while not reflecting the maximum individual progress, are still very important since they indicate the quality of a training process as a whole. The fact that a coach achieves high individual results with one or a limited group of athletes, is not necessarily an indicator of the quality of the overall approach to training.

The 3S platform, offers coaches a rock-solid science-based foundation for their programs, bringing individual and team progress rates to top national levels. While 3S training suggestions should not be viewed as an absolute dogma, the general principles implemented in 3S offer a sure path to solid performances and progression. 3S University offers Coaches further professional development opportunities, and ultimately, successful careers.